Large retailers have hit turbulence – Could this spell trouble for the sector at large?

Key highlights

The retail sector has reacted to the post-pandemic consumer, with recent headlines signaling the closure of many large-format store locations (Macy’s, Dollar Tree, and more) as a result of portfolio right-sizing, corporate restructuring, or even outright liquidation

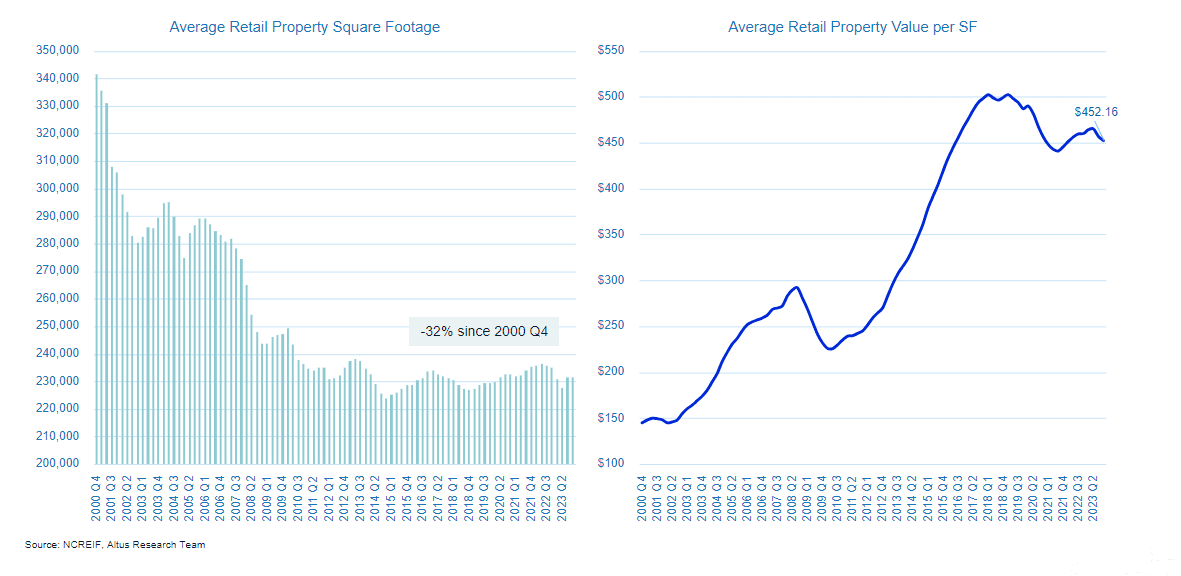

Institutional capital has reacted to these same trends, “going small”, pivoting away from the mall sector and toward higher-value smaller-footprint shopping centers

The average size of retail property owned by institutional funds has reduced by nearly one third since 2000 while the average value of owned properties has tripled on a per square foot basis over the same period

In many cases, the departure of an anchor department store or grocer can signal a dangerous inflection point in the health of an enclosed mall or shopping center

In some cases, co-tenancy agreements can accelerate foot traffic declines and catalyze a vacancy spiral

However, large retail closures have not yet necessarily been a net negative for owners of institutional retail properties in the current environment; splitting up anchors and replacing other in-line tenants at high market-to-contract rent spreads has propped up retail real estate in an era of elevated consumer spending

What is happening to retail?

Reports circulating across the commercial real estate (CRE) sector over the last year have broadcast no shortage of difficult news. The elevated interest rate environment has created headwinds for the industry at large, with transaction volumes near historic lows. These headwinds have been exacerbated by shifting demand fundamentals in certain sectors – offices remain under-utilized as companies continue to embrace remote or hybrid work. Similarly, the retail sector is working to adapt to consumers that may now favor online shopping over in-person at brick-and-mortar shops for certain goods.

Over the last few months, headlines have signaled heightened pressure in the retail sector; more specifically, the closure of thousands of large-format stores. Retailers that once dominated their respective categories are pulling back as a result of shifting consumer spending and a bifurcating American consumer, leading to portfolio right-sizing, corporate restructuring, or even outright liquidation.

In February Macy’s announced its plan to shutter 150 stores nationwide over the next 3 years as part of the company’s efforts to recover from post-pandemic losses and declining sales. The statement issued by the department store giant also mentioned the monetization of $600M to $750M of assets by the end of 2026, hinting at the potential sale of properties. Dollar Tree announced plans on March 15 to shutter 970 of its Family Dollar stores after reporting a $1.71-billion loss in the first quarter. Another discount retailer, California-based 99 Cents Only Stores LLC., announced the closure of all 371 of its stores on April 5. And on April 23, Express, Inc. revealed that it had filed for bankruptcy, with plans to close approximately 95 Express stores and all 12 UpWest locations as part of its restructuring.

If the age-old adage holds that “where there is smoke, there is usually fire”, what might these closures mean for the retail sector at large?

Will malls reach an inflection point?

The closure of 150+ Macy’s locations poses a particular challenge to mall properties. In many cases, the departure of an anchor department store can signal a dangerous inflection point in a center’s health. Co-tenancy agreements, which may give nearby retailers the option for a significant reduction in monthly rent payments or the ability to break their lease without paying a financial penalty, can accelerate foot traffic declines and catalyze a vacancy spiral. As one mall wing empties, others follow, making the prospect of backfilling in-line spaces incredibly difficult. Finding the right blend of retail, food, entertainment, and experience to ensure a mall’s mass appeal and encourage consistent foot traffic is no simple task.

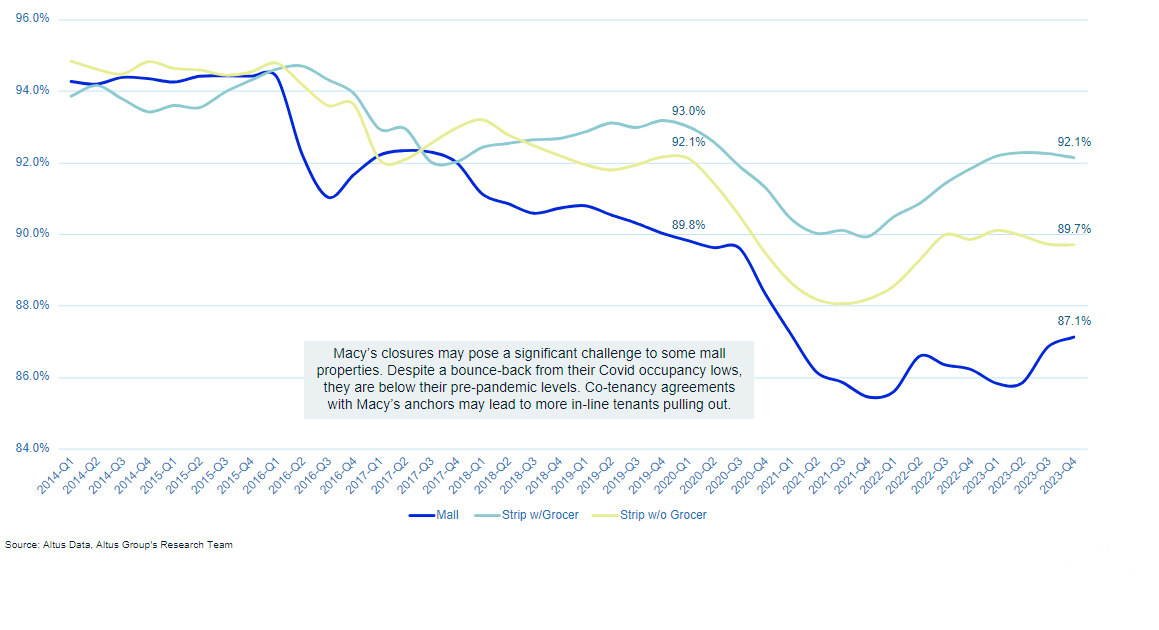

Mall properties have already seen steady decreases in occupancy over the preceding decade, and Macy’s departures could certainly exacerbate their troubles. Mall occupancy, despite a bounceback from pandemic lows, remains below the pre-pandemic level in addition to being well below that of strip centers.

Figure 1 - Declining mall occupancy

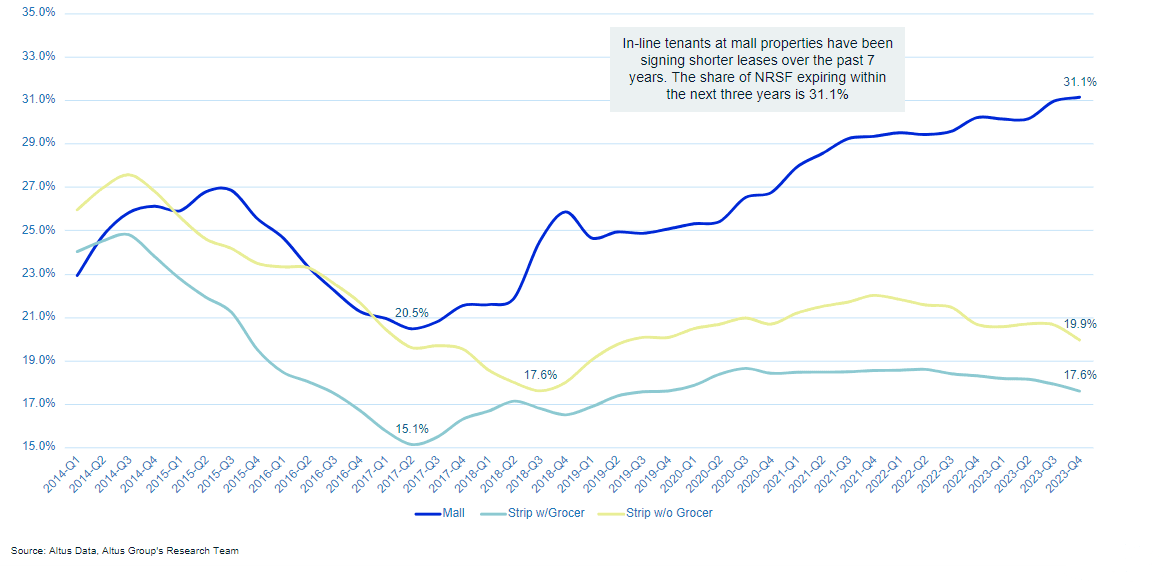

A retreat from the mall sector by institutional owners is thus hardly a surprise; mall properties also maintain other operational disadvantages, such as troubling lease turnover trends. As uncertainty plagues in-line tenants, they’ve continued to sign increasingly short leases since 2Q 2017. The share of net rentable square footage (NRSF) expiring within the next three years is nearing one-third in enclosed regional malls, up from only one-fifth. Strip centers, with and without grocers, are on an opposite trajectory.

Figure 2 - Net rentable square footage (NRSF) expiring within three years

Is the next big thing in retail “going small”?

Closures were, however, not the only highlight from Macy’s announcement – the retailer shared plans to pivot to smaller, luxury brands. This “trimming” strategy is being explored by other retailers like Whole Foods, Best Buy, and The Container Store, which have also announced plans to explore smaller formats. In the age of e-commerce, retailers have seen the cost advantages in keeping most physical inventory in the warehouse as opposed to in branded displays on retail floors.

The need for physical storefronts has not dissipated entirely; rather, the pervasive theme across many retail categories is that “less is more”. Modern physical storefronts can offer consumers more of an “experience” that cannot be replicated online, and one that can be achieved without large floorplates. Retail spending remains near all-time highs and vacancy remains near all-time lows, yet employment in the sector has remained generally flat. This is a trend that may indicate retailers are becoming more efficient with their space and labor.

Just as retailers have reacted to consumers, capital has reacted to retailers. Institutional owners of retail properties have taken note of the “less is more” approach, largely pivoting toward higher-value smaller-footprint shopping centers in lieu of capital-intensive enclosed malls. The average size of retail property owned by institutional funds has fallen by nearly one-third since 2000 while the value of owned properties has tripled over the same period.

Figure 3 - Institutional capital reacts to retailers

Ultimately, the demise of certain large-format stores does not necessarily spell doom for retail real estate. Recent estimates suggest that store openings outpaced store closures throughout 2023. In many cases, the closure of legacy retailers during a period of heightened consumer spending has been a net positive, providing ample opportunity to split up floorplates, reconfigure spaces, and capture additional rent. Market-to-contract rent spreads are positive and increasing across all major retail property subtypes, including malls. While the closure of a mall anchor in particular can compound vacancy problems quickly, thus far, institutional owners have had success backfilling and adapting former spaces to the needs of the modern consumer. But looking forward, the continued need to appeal to distinct segments of American consumers – the upscale or the value-focused – will be a primary challenge for retail.

Want to be notified of our new and relevant CRE content, articles and events?

Author

Cole Perry

Associate Director of Research, Altus Group

Author

Cole Perry

Associate Director of Research, Altus Group

Resources

Latest insights