Key highlights

Canadian residents find themselves in the grips of a housing unaffordability crisis, as demand for housing outpaces supply by an exceedingly large margin

As the housing market slows in response to high interest rates, more demand will be placed on the rental sphere, which will only exacerbate record-high rents

The removal of housing that would otherwise be available on the long-term rental market is often referred to as the ‘Airbnb effect’

The disconnect between housing supply and demand has long been cited as a primary contributor to the housing affordability issue, but many would argue that short-term rentals (STRs) like Airbnb, Vrbo, and FlipKey also play a key role

In the current market, high property values combined with heightened interest rates and inflation create a challenging environment for investors and homeowners to cover costs and protect profit margins on residential properties

Are increased regulatory controls the best or only solution to an over-zealous STR market?

Do STRs play a role in the housing affordability problem?

City centres like New York, Toronto, and San Francisco have long cemented their reputation for a competitive marketplace, especially in the housing department. These bustling urban hubs are rife with opportunity and proximity; offering residents an experience earmarked by density-driven convenience – entertainment, work, retail, and resources are almost always just a block or two away. Each neighbourhood hub has its own ecosystem that attracts prospective homebuyers, renters, and tourists alike, and it’s well understood that finding a place to live or stay will be an expensive – and at times, even difficult – proposition.

But as of late, Canadian residents face a housing affordability crisis while general cost of living continues on its upward trajectory amidst continued economic turbulence. In the current market, debt is increasingly expensive. At the same time, housing supply is unable to match the demand we’ve seen from changing demographics and increased immigration, a core factor driving the cost of living up. As a result, there are few units available for prospective buyers and renters alike, which creates a market increasingly pressurized by scarcity.

To this effect, the National Bank of Canada’s latest Housing Affordability Monitor estimated back in November that it would take an average household roughly 25 years to save for a down payment in Toronto, assuming a 25-year amortization period and a five-year term. A recent report from Ontario Chamber of Commerce reiterates this sentiment, stating that housing affordability has reached a “crisis point” in Canada’s most populous province and is “now impacting communities of all sizes across the province.” Another report ranked the city of Toronto last among other Canadian cities when it comes to being a place where young people can financially thrive. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives has also found that a person would need to make more than double the minimum wage — $33.60 an hour — to afford the rent for a one-bedroom apartment, or $40 for a two-bedroom.

As interest rates continue to climb, the housing market is expected to slow, with prospective buyers hesitant to assume the high carrying costs associated with purchasing a home in this market. Understandably, this trend will push more demand into the rental sphere, which will only exacerbate record-high rental prices. From a year-over-year perspective, the latest report from the Canadian Rental Housing Index revealed that between 2016 and 2021, the largest increases in average rents were in British Columbia (30%) and Ontario (27%). Both provinces also lead the country in the highest proportion of renters spending unaffordable or “crisis amounts” on rents and utilities.

Current conditions could, perhaps, be described as the “perfect storm” – housing affordability has long been a concern across popular Canadian cities, but is the issue now fast approaching its peak? More importantly, how did we get here? Aside from post-pandemic monetary tightening, what other factors might have contributed to this concerning crescendo of housing unaffordability? The disconnect between housing supply and demand has long been cited as a primary contributor to this issue, but many economists, politicians, and advocacy groups would argue there is another factor which also must be called into question: short-term rental (STRs).

STRs: A disruptor of the hospitality industry… and the housing market

As a residential property owner, you essentially have five options:

Live in the unit as a primary residence

Hold the unit as a secondary residence (i.e. vacation property)

Rent out the unit to a long-term tenant (one-year lease, or more)

Use the unit as a STR

Sell the unit

A homeowner’s decision to rent out a room or two to help with their monthly mortgage payment is palatable for most; however, there is growing concern that investors will purchase existing residential units with the sole intention of using them as an STR.

Can a healthy STR market and an affordable housing market co-exist? This is the question that has weighed heavily on many hot-spot regions, like Toronto, as housing prices climbed seemingly in tandem with STR demand. Commonly referred to as the ‘Airbnb effect’, local housing markets often produce inflated rents and home prices in areas where STRs are most prominent.

It’s important to note that STRs pose a great benefit to the local economy; tourism is, after all, a key economic driver and brings international exposure and investments to local jurisdictions. At the same time, STRs like Airbnb and Vrbo offer tourists and residents more variety when they are in need of temporary accommodations and have represented an attractive investment opportunity for homeowners to subsidize their mortgage payments. But this leads us to the penultimate question – is there a long-term cost to renters, the housing supply, and communities at large and, if so, does that cost outweigh the benefits? There doesn’t (yet) appear to be a clear answer to that question.

On one hand, an October 2023 research report published by The Conference Board of Canada in collaboration with Airbnb claims that Airbnb activity at the current levels “has not generated an economically meaningful increase in rents across Canada’s major cities.” The study noted that, contrary to the prevailing narrative around Airbnb listings, of the 30% increase in rents observed in their sample of neighbourhoods, less than 1 percentage point (at most) can be attributed to increased Airbnb activity.

At the same time, however, Chrystia Freeland recently weighed in on the issue, noting the importance of “relieving pressure” on the tight rental market across Canadian cities. Specifically, Freeland cited estimates from McGill University in 2019 that 31,000 units could be freed up from short-term rental platforms — particularly in Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver — through further regulation of the space. The study cited illustrated STRs as potentially problematic for the housing affordability juggernaut because they “incentivize the further financialization of real estate, whereby people buy homes not to live in, but to rent out in the hopes of gleaning better returns than they would generate from a long-term rental. Similarly, a new Desjardins report indicates that the proliferation of short-term rentals on platforms such as Airbnb and Vrbo reduces the number of units available for long-term rentals and resale markets. "From the perspective of the landlord, at a time of high and rising inflation, short-term rentals may offer them an opportunity to offset some of the rising costs because they can increase the rent more quickly than they could in the long-term rental market," said Randall Bartlett, Senior Director of Canadian economics at Desjardins. Moreover, some property owners may choose to hold onto their property if the current market doesn’t reflect the value they hope to get for their property.

The report suggests that every one-percentage-point increase in the share of Airbnbs was associated with a 2.3 per cent increase in rents. Canada has more than 235,800 unique active short-term rental listings on Airbnb and Vrbo, amounting to about 1.4 per cent of the country's housing stock or 4.9% of its long-term rentals.

According to Vancouver’s City Councilor Lenny Zhou, the influx of STRs has become a serious issue in Vancouver, as more people are renting out their principal residence on a short-term (often illegal) basis. The councilor notes that you need a valid business license to operate an STR, and it’s illegal to operate a short-term rental that isn’t your principal residence; however, many Vancouver residents are now skirting this rule. As the Vancouver market is flooded with STRs (many of which are violating regulations) while available long-term units and housing supply remain scarce, the surrounding market suffers from higher rents and lack of unit availability.

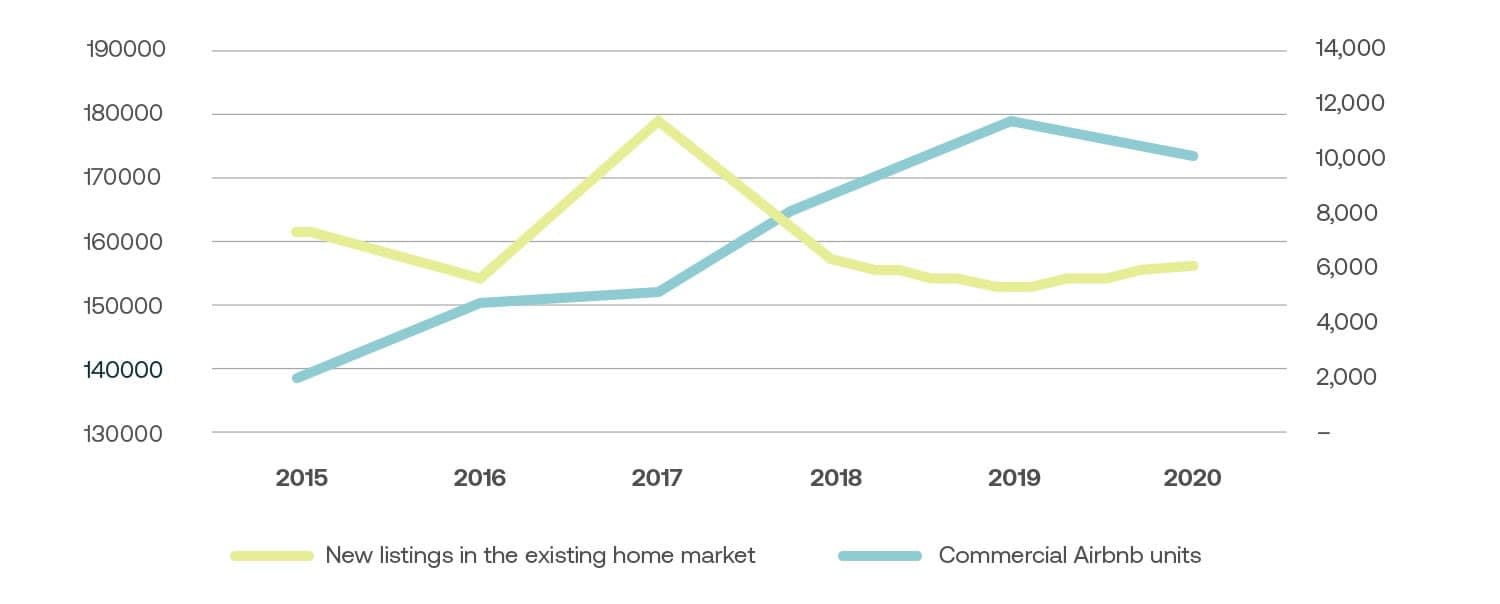

As of 2020, there were roughly 29,000 units being used for Airbnb in the City of Toronto, 11,000 of which were ‘commercial Airbnb units’, meaning these units were solely used as Airbnb rentals. The rental vacancy rate, at that time, was 1.3%, indicating an exceedingly tight rental market for those looking for long-term housing.

Figure 1: The rise of commercial Airbnb units in the City of Toronto and the fall of new listings in the resale market

Has the STR investment bubble burst?

It’s also worth noting that, perhaps, the ‘golden age’ of property investment might – at least temporarily – be over. If we look back to the 1980’s, as an example, the average cost of a home was much lower (in 1985, the average home price was $109,094 according to the Toronto Regional Real Estate Board). However, median household incomes were much lower, and homebuyers needed 25% down in 1985 with five-year fixed mortgage rates hovering around 13.25%. To put this into perspective, the Financial Post estimates that a house cost 3.41 times the median family income in Toronto in 1985. Comparatively, the average home price in the Greater Toronto Area was reported at $1,164,400 as of May 2023, while the median after-tax household income in Toronto sits at $73,000.

But between 2010 and 2020, many residents bought into what could be described as a ‘sweet spot’ in the housing market. Even as the average cost of a home increased, down payments could be as little as 5%, and interest rates remained low. This painted a pretty picture for property investments; if you could afford the down payment, you could likely purchase a property with relatively low mortgage costs, and later sell that property at a value that far exceeded what you purchased it for. Similarly, these properties could be leveraged as STRs to generate a favourable return over time.

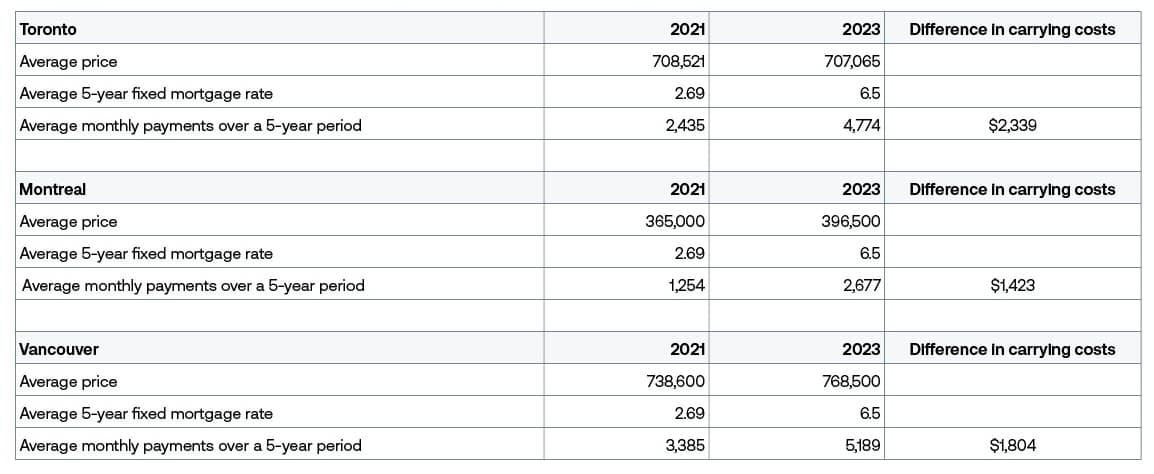

The conditions of today’s market pose an important question – do higher interest rates erode the attractiveness of STR as an investment opportunity, or perhaps the attractiveness of property ownership overall? There are, of course, alternative investments, and perhaps the return on investment no longer justifies the interest cost.

Figure 2 - Carrying costs of a condo apartment (as of September of a given year) in 3 major Canadian markets

Could tighter regulation on STRs be the answer?

Oftentimes, increased regulation is proposed as a control measure for an over-zealous STR market. In fact, emerging Airbnb regulations have been making headlines for months as major markets like New York and British Colombia have introduced new, rather unforgiving rules for STRs.

In early September the Short-Term Rental Registration Law (Local Law 18), came into effect in New York, which requires hosts to register their listings with the Mayor’s Office of Special Enforcement and requires booking platforms to ban any unregistered listings. Local Law 18 is an add-on to existing regulations which, according to city officials, have been largely ignored or violated until now. In fact, a city official claimed in a July court filing that more than half of Airbnb’s $85 million net revenue in 2022 from STRs in NYC came from “illegal” activity (however, this figure has been disputed by Airbnb). The pre-existing regulations prohibited people from renting their homes for less than 30 days unless the host was also in the home during the stay and limited rentals to no more than two guests per stay. Eligible hosts must prove they live in the dwelling they are renting out and that the home is up to municipal safety codes and other regulatory requirements. Hosts in violation of the new legislation could face fines from $1,000 to $5,000.

Similarly, in October of this year, BC proposed new legislation to help municipalities regulate short-term rentals, which includes increasing fines for hosts breaking local municipal bylaw rules to $3,000 per infraction, per day, from $1,000. All short-term rental platforms will reportedly be required to share data with municipalities to improve local enforcement. “In addition, all short-term rental platforms will have to include the business licenses and registration numbers of listings where they are required by a local government, and must remove listings without those requirements quickly,” shared a CBC report. The new regulations, which are expected to come into effect in stages spanning through late 2024, will also include a new provincial short-term rental compliance and enforcement unit.

But are increased regulatory controls the best or only solution? STRs are, after all, beneficial to the economy in many ways with respect to tourism and providing a ‘home away from home’ for visitors whose needs would unlikely be met by traditional hotel accommodations. Moreover, the complete elimination of the STR is an unrealistic (and perhaps misinformed) goal for any jurisdiction. To this effect, the Desjardins report suggests that policy crackdowns on STRs have had mixed results in different jurisdictions around the world, but restricting the use of second or third properties for short-term rentals has seemingly been the most successful measure in bringing more units back into the long-term rental market. With this in mind, Desjardin proposes the government partly restricts commercial non-principal short-term rentals, strictly enforces penalties for non-compliance, and holds STR platforms accountable to help ease the housing crisis.

There is also, perhaps, an opportunity to re-invest some of the taxes and fees collected from STR property owners back into the housing market, as well as a case to be made on the development side. If we know that some (or many) units in any development will surely be utilized for STR versus long-term rentals or principal residence, shouldn’t it be standard practice to bake this allocation into development plans?

For example, municipalities across Canada are required to plan for expected growth in new households – let’s take the City of Toronto for example. The figure below shows that as of 2020, it was expected that there would be 82,400 new households in the city between 2016 and 2021. Therefore, the city would plan to meet this demand through new development. Indeed, the city saw almost 82,000 units built over this period. However, there were also almost 8,000 new units added to the short-term rental market through Airbnb alone. In addition, 18,218 units were used for other purposes, such as student housing and/or held vacant. If you account for these other uses, the City of Toronto would have needed 108,618 units to be built over this period.

Figure 3: City of Toronto housing needs between 2016 and 2021

This observation begs the question – STR regulations aside, shouldn’t STRs be a key consideration for urban planners, developers, and policymakers as they map out zoning and residential development controls and incentives within major cities, like Toronto?

Want to be notified of our new and relevant CRE content, articles and events?

Author

Diana Petramala

Director, Research, Valuation & Advisory, Economic Consulting

Author

Diana Petramala

Director, Research, Valuation & Advisory, Economic Consulting

Resources

Latest insights